Where to Start Hand-Writing a Parser (in Rust)

2021-05-05

🕓 43 min (8424 words)

I'm in the Rust community Discord server.

Particularly, I hang around in their language development channel (regularly called #lang-dev, but its name is ever changing).

The folks in the server come with varying experience in Rust, and #lang-dev is frequented by Rustaceans of vastly different skill levels and knowledge backgrounds when it comes to actually working on a programming language.

In my experience, the Rust community is incredibly kind and usually glad to help out with questions.

Some questions however, especially beginner ones, keep coming up again and again.

Regarding parsing, there are a number of great resources already.

To mention a few, together with some guesses on why they might leave some of #lang-dev's visitors' questions open (if you are a beginner and some of these words don't mean anything to you yet, don't worry. We'll get there.):

-

Crafting Interpreters is an absolutely fantastic read. Code examples are in Java and C however (also, the C compiler they develop is of very explicitly single-pass, which often makes it difficult for people to use it as guidance for their languages if the language design does not fit that model well. But that's less related to parsing).

-

Writing a Simple Parser in Rust is very beginner-friendly, as it describes the author's own experience coming up with their parser. The parsing result is a homogenous syntax tree, which I personally like a lot, but, based on Rust Discord conversations, a strongly typed AST seems to be easier to conceptualize for many beginners because it gives you concrete things from your language to talk about (like a

Functionor aVariable). More generally, the post is focused on parsing arithmetic expressions.There is more to most languages than those, though, and dealing with precedence and associativity is often the source of a lot of confusion. The lexer implementation also vastly simplifies in this context, and is done by matching individual characters. That is by all means sufficient for the use case, but does not help beginners with lexing identifiers, escaped string literals, or even just floating point numbers (optionally with scientific notation), even less with handling conflicts between different classes of tokens (such as keywords which look like identifiers).

-

Make a Language is very detailed, but skips from lexer-less string-based parsing directly to using the

logoscrate.

While I'm on the topic of other resources, the rust-langdev repository is a collection of language development-related crates organized by category, also featuring a "Resources" section with further links on a bunch of topics. Go check it out!

🔗This Post is

- An introduction to programming language parsing in which we hand-write a parser and run it on some real input.

- A starting point, leaving lots of room for own experiments and further reading.

- Intended as a collection of partial answers I have given in the Discord over time, to have a more comprehensive example and explanation to refer people to.

- Accompanied by a public repository containing the full implementation.

🔗This Post is not

- Conclusive. Several problems we are tackling here can be solved in multiple ways and I present only one place to start.

- A tutorial on writing production parsers, or an in-depth tutorial on any of the areas it covers really.

- About parser generators. We will do all of the parsing by hand.

🔗Blog Repository

The parser built in this article is publicly available at https://github.com/

🔗A High-Level View

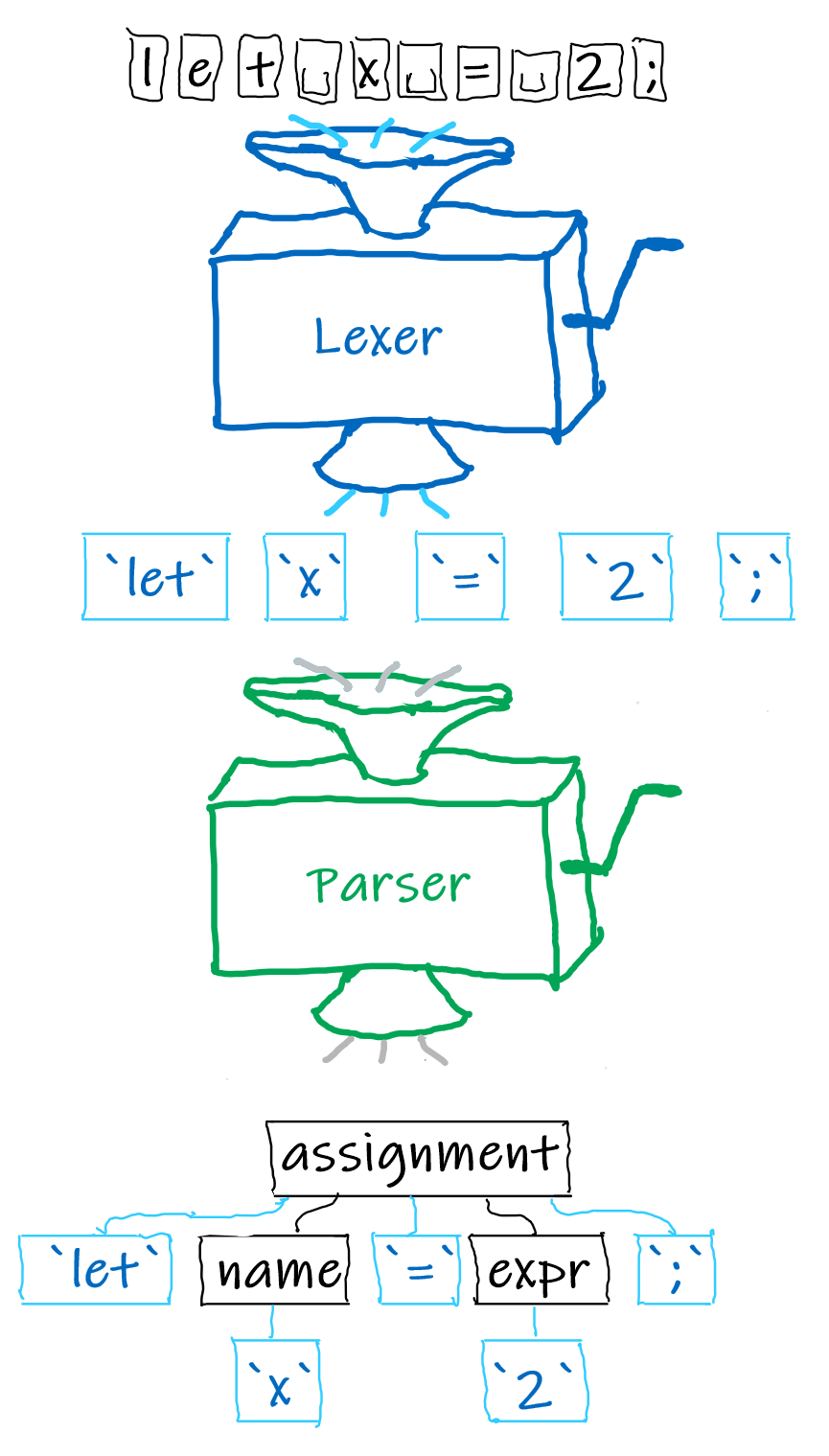

By "parsing", we mean the process of transforming some input text, for example a source file of code in your language, into a syntax tree.

Why transform the text? Because working with individual characters gets really tedious very quickly, and also introducing additional structure to, e.g., the input to a compiler for your language, is very useful to said compiler (or language server, or whatever you want to build) because it can operate on a higher level of abstraction.

Why a tree? Programs in most languages are already organized hierarchically.

Think about Rust: You have crates (libraries or binaries), which can house multiple modules.

Each module can define an arbitrary number of items such as structs, traits, functions or constants.

A function is a sequence of multiple statements like variable assignments, loops, conditionals (if), etc[1].

Statements are subdivided further into their components, until at some point we reach some kind of "basic building blocks" of our language and can go no further.

For example, a variable assignment in Rust consists of the keyword let, a variable name, an equals sign =, an expression that represents the new value of the variable, and a closing semicolon ;.

The expression could be a function call, a combined expression like an addition of two numbers, or just a literal (a literal is when you write an explicit value of some data type, like 3, "Hello World!" or Foo { bar: 2 }).

Inside of a struct are its fields, but there is even more hierarchy that can be hidden in a struct definition.

Consider a generic struct Foo<T, U>.

The type definition of this struct includes the struct's name (Foo), as well as a list of generic parameters.

If you place some restrictions on T or U with a where bound, that bound becomes part of the struct definition too!

Trees are exactly the structure to represent how a program in your language is built up from its basic blocks layer by layer. You need somewhere to start, like a crate in Rust, but we will just start out with a single file which can contain multiple functions. This starting point becomes the root of the syntax tree. When parsing a program, it's all about piecing together more and more parts of the tree, branching out every time a part of the program is made up of multiple smaller parts (so, always). Below is an illustration of a syntax tree for a file that contains a function with a variable assignment:

🔗"Excuse me, there's a Lexer in your Parser"

The first point of confusion that commonly arises is that what is colloquially referred to as "parsing" quite often includes not one, but two components: a lexer and a parser.

A lexer looks at the input string character by character and tries to group those characters together into something that at least has a meaning in your language.

We'll call such a group of characters a token.

Sometimes, a token will just be a single character.

A semicolon or an equals sign already mean something to you when you program, while the individual letters "l", "e" and "t" probably don't in most contexts.

The lexer will recognize that sequence of characters as the let keyword and will put them in a group together as a single token.

Similarly, the lexer will produce a single "floating point number" token for the input 27.423e-12.

The parser's job is then to take the meaningful tokens kindly created by the lexer and figure out their hierarchical structure to turn them into a syntax tree. I've described most of the general idea above already, so let's finally make one!

Edit: It was pointed out to me that I should probably at least mention that you don't have to explicitly make a separate lexer and parser. Lexing and parsing actions or phases are conceptually part of the majority of parsers, but there are systems that don't split them as rigorously or even actively try to integrate them as closely as possible. Scannerless parsers are a broad category of examples of this, which also contains several parser generators. If you do this, this makes it much easier for example to parse multiple languages combined. We are not doing that in this post, and since this is intended to be an introduction to lexing and parsing I'll keep the two separate in our implementation.

🔗Implementing our Lexer and Parser

We'll set up a new crate for our parsing experiments:

> cargo new --lib parsing-basics

Since we need tokens for the parser, we start with the lexer and make a lexer module, which in turn has a token module.

In there, we make an enum of the kinds of tokens we will have:

// In token.rs

You can see we have a lot of single-character tokens in there (including left and right brackets of all types), and then the groupings of strings and comments, numbers, and identifiers and keywords, as well as kinds to group things like && or != together.

We also have the Error kind in case we see a character we don't understand, and the Eof kind, which stands for "end of file" and will be the last token produced by the lexer.

Next, we will do something that will come in handy a lot during our implementation: we will define a macro for referencing token kinds:

;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

=> ;

}

This is a long list, but from now on we can for example refer to the "less or equal comparison" token kind as T![<=].

Not only does that save a lot of typing, in my opinion it is also a lot more fluent to read.

The first use of our new macro will be implementing a nice Display representation for TokenKind:

Again we've got ourselves a small wall of text, but we can now add a small test to check everything works as it should so far:

🔗Tokens

We can now go to define our tokens.

They will store the kind of token, of course, as one of the TokenKinds we just defined.

The other thing we'll want to know from our tokens is, well, what they are.

For example, if in the parser we see a token that we did not expect, we want to produce an error, which benefits a lot from including in the error message what the user actually typed.

One option would be to use Rust's amazing enums and include things like the name of an identifier or numbers in their respective variants.

I personally don't like this approach as much, because it makes tokens be all over the place - some have just their kind, some have an additional string, some have a number, ...

What about just including the the string of a token in all of the tokens?

This would make the tokens equal again, but also we'd have to take all of these tiny strings out of the string we already have - the input string.

Strings mean allocations, and with strings our tokens will not be Copy.

Instead, we will make use of spans.

A span is simply two positions representing the start and the end of the token in the input string.

Rust has a type like this in its standard library: Range.

However, Range has some quirks that make it less nice to work with than I would like (in particular, for reasons that have no place in this post, it is also not Copy even if you make only a Range<usize>).

Let's thus make our own small Span type that can be converted to and from Range<usize>:

// In token.rs

We can also add the ability to directly index strings with our spans:

Our tokens will then have a TokenKind and a Span and, given the input string, will be able to return the text they represent via the span:

We'll make Token's Display forward to its kind, but let its Debug also show the span:

🔗Lexer Rules

Now, let's talk about how to compute the next token for some input.

For the single-character tokens, that seems quite easy - we see a +, we make a plus token.

But what about longer and more complicated tokens, like floating point numbers?

And what the next few characters could be multiple kinds of token?

Seeing a = character, we would classify that as an "equals sign" token except there might be another = following it, in which case maybe it's a comparison operator (T![==])?

Or maybe it's just two equals signs next to each other?

When we see let, how do we know it's a keyword and not the name of a variable?

If we look at some common lexer and parser generators to see how they have you write down parsing rules (look, just because we're not using one, doesn't mean we can't take a peek, eh?), we find a large variety of regular expressions.

Now, I may be fine with using regular expressions for the more complex tokens, but for something as simple as + they do seem a bit overkill.

Also, these generators have the advantage that they can optimize the regular expressions of all tokens together, which I will not do by hand in this blog post (or probably ever).

Let start with the simple cases and work our way up.

In our lexer mod, we create a (for now fairly uninteresting) Lexer struct and give it a method to lex a single token:

// In lexer/mod.rs

;

We will put all the lexer rules in a separate file, so we'll implement unambiguous_single_char in a new lexer module rules:

// In lexer/rules.rs

/// If the given character is a character that _only_

/// represents a token of length 1,

/// this method returns the corresponding `TokenKind`.

/// Note that this method will return `None` for characters

/// like `=` that may also occur at the first position

/// of longer tokens (here `==`).

pub const

The method is essentially the reverse of the Display implementation, but only for tokens that are one character long and cannot be the start of anything else.

So it includes + and most of the brackets, but, for example, it does not include =, because of the possible ==, and /, because that can also be the start of a comment.

Angle brackets are absent because they can also be the start of <= and >=[2].

We can also start thinking about what to do when the user inputs something we don't know (yet).

If we can't make a token at the start of the input, we'll look ahead until we can and emit an Error token for the characters we've had to skip over:

/// Always "succeeds", because it creates an error `Token`.

At long last, we can write a function that works through an entire input string and converts it into tokens:

Let's create a small integration test for the tokens that should work already:

// In tests/it.rs

use ;

/// walks `$tokens` and compares them to the given kinds.

🔗Making our Lexer an Iterator

While our lexer produces the correct kinds of tokens, currently all tokens are created with the span 0..1.

To fix that, we'll have to keep track of where the lexer is currently positioned in the input string.

We'll take this opportunity to have the lexer take a reference to the input string.

This means that it will now need to have a lifetime, but also has advantages - it lets us resolve tokens to their text through the lexer, and we can make the lexer an iterator:

// In lexer/mod.rs

At this point, we should be able to adapt our tests to pass the input to the lexer and they should pass as before.

Note that all of our Lexer methods will now take &mut self, because we have to update our position.

You'll have to make the lexer variables mut in the tests so everything keeps working.

// In tests/it.rs

Let's actually fix the spans now:

// In lexer/mod.rs

/// Returns `None` if the lexer cannot find a token at the start of `input`.

/// Always "succeeds", because it creates an error `Token`.

We'll also add a small test for token spans:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗Whitespace

Whitespace is special enough for us to handle on its own, mainly because there will probably be a lot of it and it is also a class which can never conflict with anything else - either a character is whitespace, or it is not. Successive whitespace characters are also grouped together into a single token:

// In lexer/mod.rs

/// Returns `None` if the lexer cannot find a token at the start of `input`.

We can copy one of our basic tests and add some whitespace to see this works:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗Other Rules

We've seen before that for the remaining tokens we need a general mechanism to determine which class they belong to. We'll say that a general lexer rule is a function which returns if and how many input characters it could match to the token kind it is for and start with the remaining one- and two-character tokens and the keywords:

// In lexer/rules.rs

pub

pub

In the lexer, we plug in the new rules where the input is neither whitespace nor clearly a single character:

// In lexer/mod.rs

If the simpler cases don't trigger, we iterate over all our rules and, for each rule, check if it matches the input.

We then select the rule that matches the longest piece of the input, that is, the most input characters.

This choice is commonly known as the "maximal munch" principle and makes it so two successive = become ==[3].

Moreover, it is consistent with grouping a sequence of digits all together as an Int, or letters as an Identifier (which we'll do next).

Note also that we decide to resolve conflicts between tokens of the same length by choosing the rule that was written first.

We will write the rules from least to most general, so things like identifiers will be plugged in at the back.

Speaking of identifiers, we'll make some quick tests for our new rules and then we'll finally handle them. Here are the new tests:

// In tests/it.rs

Let's get to the big boys.

For this post, we will use regular expressions here.

This means we need to add the regex crate to the project.

Since we'll need to put our regexes somewhere, we also add the lazy_static crate.

While we're at it, we add unindent as a dev-dependency as well.

unindent is a small utility to, well, unindent text, to help us write a full test for the lexer after we've added the missing rules.

Because users of our lexer don't run the tests, they don't need to have unindent, which is why it doesn't go into the regular dependencies:

[]

= "1"

= "1"

[]

= "0.1"

We add a matching function for regex-based rules which queries the regex (conveniently, Regex::find returns an Option) and the regexes themselves.

We then make new rules that use match_regex and extend our ruleset with them.

I skipped T![int] integer literals with the regexes and instead gave them their own little rule which works the same way we handle whitespace (it's still important to have a rule for this though, because integers and floats can conflict):

// In lexer/rules.rs

lazy_static!

pub

Have a look at the regex crate's documentation to learn how the regular expressions are specified.

I write them in raw string literals, which go from r#" to "#.

All regular expressions are anchored with the starting ^, which forces them to match the input from the start and excludes matches anywhere else later in the input.

Then, a string is a sequence of characters in quotation marks ("), optionally including an escaped quotation mark (\") or backslash (\\).

A line comment starts with // and ends at the end of the line.

A floating point number is some digits, maybe followed by a period and more digits, or alternatively it may also start with the period.

It may be followed by E or e, an optional sign and more digits to allow scientific notation.

An identifier is any variable name, for which we require to start with a letter or underscore, and then also allow digits for the characters after the first.

Time to try it out! We'll add two tests, a function and a struct definition:

// In tests/it.rs

Note that the comment before the fn test is correctly recognized as a comment, while in the assignment to x there is a single / for division.

This is because the comment is longer than a single slash, so it wins against the single character rule.

The same happens for the floating point number in the same assignment.

Our keywords are also recognized correctly.

They do match as identifiers as well, but their rules are declared earlier than the identifier rule, so our lexer gives them precedence.

🔗Some Source Text

We'll extend that last text with a few checks for identifiers to illustrate how to get back at the input string from a token:

One lexer, done.

🔗The Parser

Our next big task is to re-arrange the lexer tokens into a nice tree that represents our input program.

We'll need a little bit of setup, starting with defining the AST we want to parse into.

All of our parser-related stuff will go into a new parser module with submodules, like ast:

// In parser/ast.rs

We have 3 kinds of literal, corresponding to T![int], T![float] and T![string].

Identifiers store their name, and function call expressions store the name of the function and what was passed as its arguments.

The arguments are themselves expressions, because you can call functions like sin(x + max(y, bar.z)).

Expressions with operators are categorized into three classes:

- Prefix operators are unary operators that come before an expression, like in

-2.4or!this_is_a_bool. - Postfix operators are also unary operators, but those that come after an expression. For us, this will only be the faculty operator

4!. - Infix operators are the binary operators like

a + borc ^ d, whereaandcwould be the left-hand sideslhs, andbanddare the right-hand sidesrhs. This is not the only way to structure your AST. Some people prefer having an explicitExprvariant for each operator, so you'd haveExpr::Add,Expr::Sub,Expr::Notand so on. If you use those then of course you don't have to store the kind of operator in the AST, but I'm going with the more generic approach here, both because I personally prefer it and because it means less copy-pasting and smaller code blocks for this article.

Note that the AST discards some information:

When calling a function bar(x, 2), I have to write not only the name and arguments, but also parentheses and commas.

Whitespace is also nowhere to be found, and I can tell you already that we will not have any methods that handle comments (well, apart from figuring out how we don't have to deal with them).

This is a major reason why the AST is called the abstract syntax tree; we keep input data only if it matters to us.

For other application, like an IDE, those things that we throw away here may matter a great deal, e.g., to format a file or show documentation.

In such cases, other representations are often used, such as concrete syntax trees (CSTs) that retain a lot more information.

🔗Parser Input

I can tell you from personal experience that having to manually skip over whitespace and comments everywhere in a parser is not fun.

When we made the lexer tests in the last section, we filtered out all such tokens from the lexer output before comparing them to what we expected, except where we specifically wanted to test the whitespace handling.

In principle, our parser will have a Lexer iterator inside and query it for new tokens when it needs them.

The Iterator::filter adapter that we used in the tests has the annoying property, however, that it is really hard to name, because its predicate (the function that decides what to filter out) is part of its type.

We will thus build our own small iterator around the lexer, which will filter the tokens for us:

// In parser/mod.rs

I don't think we've used the matches! macro before.

It is basically just a short form of writing

match next_token.kind

though I admit !matches! always looks kinda funny.

Our parser can then be built like this:

// In parser/mod.rs

The downside of the "lexer as iterator" approach is shining through a bit here, since we now have to carry around the 'input lifetime and the where bound (and also we had to make TokenIter in the first place).

However, we'll mostly be able to forget about it for the actual parsing methods.

Peekable is an iterator adapter from the standard library, which fortunately can be named more easily than Filter.

It wraps an iterator and allows us to peek() inside.

This lets us look ahead one token to see what's coming, without removing the token from the iterator.

We will use this a lot.

Let's start with the basic methods of our parser:

To start building our parse tree, the first step will be expressions. They'll end up occupying quite a bit of space, so they also go in their own module:

// In parser/expressions.rs

As you can see, we'll be using peek() to figure out what expression is coming our way.

We start with the most basic expression of them all: literals

lit @ T! | lit @ T! | lit @ T! =>

I use two matches here so I can share the code for actions we have to take for all literals, which is resolving their text and creating an ast::Expr::Literal expression for them.

The lit @ T![int] syntax is something that you may not have come across before.

It gives a name to the kind that is matched, so that I can use it again in the second match.

The result is equivalent to calling let lit = self.peek() again at the start of the outer match.

In the inner match, we create the correct ast::Lit literal types depending on the type of the token.

It does feel a bit like cheating to use a function called parse() to implement our parser, but it's what the standard library gives us and I'm for sure not gonna write string-to-number conversion routines by hand for this post.

Even if I wanted to, other people have already done that work for me - for your implementation, you might also want to have look at lexical or even lexical_core.

Next on the list are identifiers, which are interesting because they might just be a reference to a variable bar, but they might also be the start of a call to the function bar(x, 2).

Our friend peek() (or, in this case, at()) will help us solve this dilemma again:

T! =>

If the token immediately after the identifier is an opening parenthesis, the expression becomes a function call. Otherwise, it stays an sole identifier. Remember that we filtered out any whitespace so the parenthesis will actually be the token right after the ident.

For the calls we loop for as long as there are arguments (until the parentheses get closed) and parse the argument expressions recursively.

This is what allows us to write my_function(x + 4 * y, log(2*z)), because the recursion will be able to parse any, full expression again.

In between the arguments we expect commas and at the end we skip over the closing paren and make an ast::Expr::FnCall node for the input.

Grouped expressions (expr) and prefix operators are fairly straightforward, because they also mostly call parse_expression recursively.

What is interesting about grouped expressions is that they will not need an extra type of node.

We only use the parentheses as boundaries of the expressions while parsing, but then the grouped expression becomes the node for whatever is inside the parens:

T! =>

op @ T! | op @ T! | op @ T! =>

Full code of parse_expression so far:

What we have now is enough to write our first test for our new parser:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗Binary Operators

I'm gonna get a bit philosophical for this one, y'all ready? Ahem. What really is a binary operator? Sure, it's an operator that goes in between to operands. But, from a parsing perspective, it's a token that extends an expression.

Imagine the input -x + 3 * y ^ 2.

With what we have now, we get as far as parsing -x as a unary operator on an identifier, because that's the biggest unit you can get without infix operators.

Seeing that the next token is a + tells us that the expression we are parsing is actually longer than that, and that after the + there should be another expression; the right-hand side of the addition.

In our first attempt at parsing binary operators, we will try to follow this view by adding an "operator loop" to parse_expression.

The entire match we have built so far becomes a potential left-hand side lhs of a binary operator, and after we parse it we check if the following token is an operator.

If so, we continue parsing its right-hand side and build a corresponding ast::Expr::InfixOp node:

// In parser/expressions.rs

If we add a small test, we see that we can now parse longer, combined expressions.

To tests, we'll implement Display for our AST such that expressions are always put in parentheses:

// In parser/ast.rs

This test now passes:

// In tests/it.rs

However, if we add some more expressions, we'll see that not all of them get parsed as we would expect to following our intuitions about maths:

Currently, we're extending the expression recursively unconditionally on seeing any operator.

Because the recursion happens after the operator, to parse the right-hand side, all our binary expressions are right-associative and ignore operator precedence rules like * being evaluated before +.

That said, this isn't all that surprising, giving that parse_expression currently has no way of knowing an operator's precedence.

Let's fix that:

// In parser/expressions.rs

For all operators, we define how tightly they bind to the left and to the right.

If the operator is a pre- or postfix operator, one of the directions is ().

The general idea is that the higher the binding power of an operator in some direction, the more it will try to take the operand on that side for itself and take it a way from other operators.

For example, in

4 * 2 + 3

// 11 12 9 10

the binding power of 12 that * has to the right wins against the lower 9 that + has to the left, so the 2 gets associated with * and we get (4 * 2) + 3.

Most of the operators bind more tightly to the right than to the left.

This way we get

4 - 2 - 3

// 9 10 9 10

the right way round as (4 - 2) - 3 as the 10 that - has to the right wins against the 9 it has to the left.

For right-associative operators like ^, we swap the higher binding power to the left:

4 ^ 2 ^ 3

// 22 21 22 21

is grouped as 4 ^ (2 ^ 3) as 22 wins against 21.

How can we implement this into our parse_expression?

We'll need to know the right-sided binding power of the operator that triggered a recursion which parses a new right-hand side.

When we enter the operator loop, we check not only if the next token is an operator, but also its left-sided binding power.

Only if this binding power is at least as high as the current right-sided one do we recurse again, which associates the current expression with the new, following operator.

Otherwise we stop and return, so the operator with the higher right-sided binding power gets the expression.

This is hard to wrap your head around the first time. Once you get it, it's great and you will never want to do anything else again to handle expression, but it needs to click first.

Simple but Powerful Pratt Parsing by matklad, the man behind rust-analyzer, is a very good article on the topic if you'd like to get explained this again, in a different way.

In code, it looks like this:

// In parser/expressions.rs

Recursive calls for both prefix and infix operators get passed the right-sided binding power of the current operator.

The important stopping point is the if left_binding_power < binding_power { break; } inside the operator loop.

If op's left-sided binding power does not at least match the required binding power of the current invocation, it does not get parsed in the loop.

It will instead get parsed some number of returns up the recursion stack, by an operator loop with sufficiently high binding power.

Function call arguments and grouped expressions in parentheses reset the required binding power to 0, since they take precedence before any chain of operators.

For the interface of our parser, we add a small wrapper that will also call parse_expression with an initial binding power of 0:

We need to swap that in in our expression parsing tests:

// In tests/it.rs, expression tests

The test that previously failed should now pass. We'll add a few more complex expressions and test that they are also parsed correctly:

// In tests/it.rs

Postfix operators are now an easy addition:

// In parser/expresions.rs

And to check it works:

// In tests/it.rs

This will be the end of expressions for us.

If you want, try adding additional operators on your own.

Some language constructs that one might not necessarily think of as operators fit very cleanly into our framework.

For example, try adding . as an operator to model field accesses like foo.bar.

For a greater challenge, array indexing can be handled as a combination of postfix operator [ and grouped expressions.

There's all kinds of expressions left for you to do, but we now have to move on to...

🔗Statements

As a reward for our hard work on expressions, we are now allowed to parse anything that indludes an expression.

The next level up from expressions are statements, of which we will consider variable definitions with let and re-assignments without let, as well as if statements (we'll also need a representation of explicit {} scopes):

// In parser/ast.rs

We'll make a new module called hierarchy for statements and beyond and start the same way as for expressions:

// In parser/hierarchy.rs

The declaration and the let differ only by the let keyword:

T! =>

T! =>

Note how we now just call self.expression() to parse the value assigned to the variable.

It will do all the expression parsing work for us and return us a nice ast::Expr to use in our ast::Stmt.

The if case is a bit more involved, because we need to handle the condition, the statements inside the if and also possible a else.

We can make our lives a bit easier by re-using the block scope statement for the body:

T! =>

T! =>

The statement test will be our longest test so far:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗Items

Let's move up another level to items containing statements.

We'll do struct and function definitions, for which we'll also need a notion of what a type looks like in our language.

As before, our reward for doing statements is that we're now allowed to use self.statement() to parse the function body.

Time to play that same song again!

// In parser/ast.rs

As you can see, a Type is really just an identifier plus a list of generic parameters.

We use that for both function parameters and struct members, and also for the struct definition itself, to allow defining structs like Foo<T, U>.

Parsing types uses a recursive loop over the generic parameters (which are themselves types, like in Bar<Baz<T>>):

// In parser/hierarchy.rs

We'll implement struct definitions first.

They are very similar - instead of generic parameters we loop over members, which are identifiers followed by : and their type:

We can test types and struct definitions already:

// In tests/it.rs

The function case should start to look familiar to you by now; it's a loop over parameters!

Additionally, we use the same trick as for if to parse the function body:

// In parser/hierarchy.rs, `Parser::item`

T! =>

We'll add a test for functions as well:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗Files

We're running the victory lap now! We'll make a parser method to parse an entire file, as a sequence of items:

// In parser/hierarchy.rs

And a last, glorious test:

// In tests/it.rs

🔗A Retrospective High-Level View: Descending

We have built up parser from small components; basic building blocks with which built higher and higher. From individual characters we made tokens. We parsed these tokens into atoms of expressions, then into bigger, complex expressions, then statements, then items, then files.

Now we have reached the top, and it's time to look back down and see how high we have built and what we have achieved.

At the beginning of this post, I described the hierarchy of a program as files containing items containing statements and so forth. It was much easier for us to implement our parser the other way round, because that way we were able to use the smaller things to build the bigger things. But if we now follow a run of our parser, we can see it tracing the hierarchy levels from the top to the bottom.

What we have built is what is called a recursive-descent parser.

In such a parser, each thing in your language is implemented as its own function, which is called from all the other places in the language where that thing could be.

You can see this in the way we call statement() and type_() from item(), and expression() from statement() (I deviated a bit from the strict pattern by not making individual struct() and function_declaration() functions and instead inlining them into item(), same with statement()).

The only real time we break away from this paradigm is to parse expressions, where we use Pratt parsing as a more tailored algorithm for expressions with precedence and associativity.

Recursive-descent parsers are widely used everywhere, for both parsers generated by parser generators and hand-written parsers for production languages (including Rust). There are corresponding bottom-up parsing techniques, but you're less likely to see them implemented by hand. Going top-down is just a lot more straightforward to implement.

🔗Bonus: What if we did use a generator?

Before we get ahead of ourselves, I will not switch our implementation to a parser generator now. For one, there is no one crate that would be the generator to use. A whole bunch of parser generators exists, and if you're interested in trying one out I will once again refer you to this list. But also, any parser generator comes with a set of trade-offs from what language grammars you can have over what it outputs to whether you can use a custom lexer with it and, if so, what that lexer has to spit out. Parser generators can be a great way to get you started prototyping your language, but you will always get the most control with a hand-written parser, at the cost of having to implement and maintain it. Hopefully, this article can help with the latter.

Generating a lexer is a different story. Lexers are a lot more "boring", in the sense that you are less likely to do anything special in the lexer that is particular to your language. An exception may be whitespace-sensitive languages like Python or Haskell, which rely on indentation as part of understanding a program written in them. Even for those, it is usually possible to wrap a generated lexer and post-process its tokens to get what you want.

A big advantage of lexer generators is that they can optimize your token classes a lot.

Instead of running all lexer rules individually for each token (which we to when we iterate over all lexer Rules and call their matches method), a generator will compute efficient look-up structures at compile time that essentially try all rules in parallel, at a fraction of the cost.

This can give sizeable improvements in performance. Why does that matter? That may seem like dumb question, but as many people before me have pointed out, parsing is usually only a tiny part of compiler in terms of the work it has to do. A compiler has many other tasks like type checking, monormorphization, optimization and code generation, all of which are probably more effort than parsing the input file. So indeed, the absolute parsing speed less relevant inside a compiler, though that may be different in other applications like IDE-tooling.

What does matter to some extent is the throughput of your parser. Throughput refers to the number of bytes, or lines, that the parser can process per second. Assuming all files have to go through your parser, this is a limit for how fast you can continuously process input.

Anyways, let's see where we stand in terms of lexing and parsing speed.

We'll bring in the criterion library and register a benchmark with cargo:

[]

= "0.1" # old

= "0.3.4"

[[]]

= "main"

= false

In the benchmark, we'll run our lexer on a function and a struct definition.

This is not a guide to criterion, so I'll not explain this in too much detail.

The important things are we need to have some input, we need to tell criterion how long that input is so it can calculate the throughput, and then we need to run our lexer on the input under criterion's scrutiny:

// In benches/main.rs

use Lexer;

use Duration;

use unindent;

use ;

criterion_group!;

criterion_main!;

Your mileage may vary, but on my machine I get:

lexer/function time: [9.5872 us 9.6829 us 9.7927 us]

thrpt: [23.081 MiB/s 23.342 MiB/s 23.575 MiB/s]

lexer/struct time: [2.4278 us 2.4652 us 2.5161 us]

thrpt: [13.266 MiB/s 13.540 MiB/s 13.749 MiB/s]

This already shows use something interesting - while the smaller struct definition lexes faster in absolute time, the throughput criterion shows for it is lower!

Obviously, our lexer isn't doing anything differently between the two inputs.

But something, be it the distribution more whitespace or more unique single-character tokens or more rule-based tokens or something else, gives the struct definition a worse profile than the function definition.

Let's bench the parser as well:

// In benches/main.rs

// Edited

criterion_group!;

And here the result:

parser/file time: [30.932 us 32.062 us 33.348 us]

thrpt: [10.209 MiB/s 10.619 MiB/s 11.007 MiB/s]

You can see that the parser takes more time overall because it does additional work (building the parse tree, figuring out what to parse next), but runs at about the throughput of the slower of the two lexer results (a bit less, due to the extra work). We don't know for sure, but unless we've hit the exact performance of our parser with that of the lexer, it seems like our parser could do more if the lexer was lexing tokens more quickly.

The aforementioned lexer rule optimizations are nothing I would do by hand.

If we bring in rayon and try to "manually" run our rules in parallel using concurrency, this does the opposite of helping:

lexer/function time: [518.46 us 520.06 us 522.20 us]

thrpt: [443.21 KiB/s 445.04 KiB/s 446.41 KiB/s]

change:

time: [+5183.5% +5251.9% +5312.1%]

(p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [-98.152% -98.132% -98.107%]

Performance has regressed.

lexer/struct time: [134.49 us 135.01 us 135.82 us]

thrpt: [251.66 KiB/s 253.16 KiB/s 254.14 KiB/s]

change:

time: [+5153.5% +5251.2% +5342.9%]

(p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [-98.163% -98.131% -98.097%]

Performance has regressed.

That does not look good! Threads have considerable overhead, so for something as small as our lexing this is not the way.

Let's instead try an optimizing lexer generator.

Unlike the entire zoo of parser generators, there is a clear winner for pure lexing:

I think I have not met a single person not using logos for this.

We'll bring it in as a dependency

[]

= "1"

= "1"

= "0.12" # <- NEW!

and set up a new lexer submodule to define a logos lexer:

// In lexer/generated.rs

use TokenKind;

use crateT;

use Logos;

pub

In the main lexer module, we rename our old lexer to CustomLexer and implement a small LogosLexer that wraps the lexer generated by logos and maps its tokens to our tokens (so we don't have to change everything else):

// In lexer/mod.rs

The spanned() function that we call on the LogosToken::lexer generated for us by logos turns the generated lexer (which is also an iterator, like ours) into an iterator that yields pairs of (token_kind, span).

Because we have already defined a method to get the TokenKind of a LogosToken, these pairs are easy to convert to our Tokens.

The rest of the iterator implementation is similar to the CustomLexer one: running our rules is now replaced with calling the generated lexer, we stick an extra EOF token at the end, done.[4]

We can now quickly toggle between either lexer by defining the newly freed type name Lexer as an alias for the lexer we currently want:

// In lexer/mod.rs

pub type Lexer<'input> = ;

// pub type Lexer<'input> = CustomLexer<'input>;

This should get us back to working.

The unknown_input and the token_spans test will fail, because logos does not aggregate consecutive unknown tokens, but everything else should work.

Time to see if using logos makes a difference.

Let's run the benchmark again, with the alias set as above:

lexer/function time: [1.7565 us 1.7922 us 1.8295 us]

thrpt: [123.54 MiB/s 126.11 MiB/s 128.67 MiB/s]

change:

time: [-82.441% -81.851% -81.304%]

(p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+434.87% +451.00% +469.50%]

Performance has improved.

lexer/struct time: [601.18 ns 609.49 ns 618.23 ns]

thrpt: [53.990 MiB/s 54.765 MiB/s 55.522 MiB/s]

change:

time: [-76.353% -75.657% -74.984%]

(p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+299.74% +310.80% +322.89%]

Performance has improved.

parser/file time: [15.714 us 15.944 us 16.230 us]

thrpt: [20.977 MiB/s 21.354 MiB/s 21.667 MiB/s]

change:

time: [-44.596% -41.849% -38.840%]

(p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+63.505% +71.965% +80.493%]

That's a 3x to 4.5x improvement for the lexer! Interestingly, function definitions still have about twice as much throughput as struct definitions. Our parser also got a nice boost, though the improvement is noticeably smaller. I did not aim for efficiency in this post, but rather understandability, and it's showing a bit.

We still see, however, the parse time being almost cut in half, even though we didn't make a single change to the parser.

This means that indeed the lexer was slowing us down previously, and is not anymore when using the lexer generated by logos.

Because you can do whatever you can think of in the LogosLexer wrapper that we defined, logos is a very viable choice to use under the hood of your hand-written parser implementation.

🔗Terms and Conditions

There are a lot of parsing techniques, parser generators and just language-related concepts out there, and if you're now continuing on your own language adventures you'll surely come across many of them. If you're looking for something specific, or maybe just so you've heard these names before and have a rough idea what they mean, here's a small list of things you might encounter:

-

The most general description of a language is a grammar. Because "literally any grammar" is quite a lot, and definitely includes languages that are really hard to handle algorithmically, the first subset of languages we often restrict ourselves to is the class of the context-free grammars (CFGs). These consist of non-terminal symbols that represent things in your language like

ExprorType, with rules how to transform them into sequences of other non-terminals or terminals. A terminal defines the concrete syntax of something, like an identifier or a semicolon;.Grammar rules for CFGs are usually written down in some version of EBNF, but you'll probably be able to read most notations that follow a

Thing -> Some Combination "of" OtherThings+ ";"notation. Many notations include some features from regular expressions to be more concise. Our struct definitions, for example, would look likeStructDefn -> "struct" Type "{" (Member ",")* Member? "}". -

Moving to parsers, you will probably see LL(k) and LR(k) parsers or parser generators. LL parsers work very much in a similar way to our hand-written parser, but use a more general mechanism to determine which language element needs to be parsed next (compared to us hard-coding this for, e.g., function and struct declarations).

LR parsers are a kind of bottom-up parser and work very differently. They have a stack onto which they push terminal symbols, and when they've seen enough terminals to put together a full grammar rule they apply the rule "in reverse", pop all the terminals and replace them with the non-terminal on the left-hand side of the rule.

For both LL(k) and LR(k) parsers, the k is the number of tokens they are allowed to

peek. In our case, k is 1 - we only ever look at the very next token after the current. Languages that can be parsed with LL(k) and LR(k) are a subset of the languages that you can express with CFGs, so your grammar must be unambiguous with k tokens of look-ahead when you want to use one of these parsers. LL(k) is a subset of LR(k), but only if the k is the same. In practice, k is often 1 for generators as well. -

While LL parsers are mostly used as-is, for LR parsers people have developed several "restricted" versions that allow more efficient parsers, but can handle less languages than full LR. The first level are LALR(k) parsers. SLR(k) parsers accept an even smaller set of languages.

-

Parsing expression grammars, or PEGs, are a different formalism that look a lot like CFGs, but add some requirements on how to parse grammars that would otherwise be ambiguous. They have some fun quirks, are otherwise fine to use, but are about as good or bad at parsing expressions than other parser generators. There's some Rust ones on the list if you wanna try one out.

🔗A Note on Error Handling

As we have written it now, our parser will panic when it encounters something it doesn't understand.

This is something all of us do from time to time, and there's no need to be ashamed about it.

Learning something new is hard, and if you've made it through this entire post as a beginner, then you have pushed the boundaries of your comfort zone more than enough for a day, so give yourselves some well-earned rest and maybe have some fun playing around with what we have made.

To wrap this back around to parsing; a "real" parser of course can't just crash on error. If the parser is for a compiler, for which invalid input programs are useless, it may stop parsing, but it shouldn't just die. Considering the user experience of using our parser is also important to consider. We are all spoiled by Rust's tooling, which we will not be able to "just" / quickly imitate. But some kind of user-facing errors are a must for any parser, and you should always strive to give the best feedback you can when something fails.

For our parser, this post is already very long and I don't want to shove an even more overwhelming amount of information down you people's throats. If this is received well, adapting our parser to handle errors could be a nice topic for a follow-up article. Until then, try not to panic when you're hitting a wall on your language development journey. If you do get stuck somewhere, remember that there is always someone around in the community that can and will be happy to help you. And instead of banging your head against that wall, maybe go outside, look at some real trees, and ponder why they are upside down.

-

In Rust, this is somewhat confusing, because most expressions can also be statements. For example, you can

breaka value from aloop. ↩ -

We will not add binary left- and right-shift operators (

<<and>>) in this post, but if we did they'd be another source of ambiguity here. ↩ -

Be careful for which character sequences you introduce combined lexer tokens. Equality operators are usually fine, but for some character combinations munching them maximally may clash with other viable implementations. See the "Drawbacks" section of the Wikipedia article for some examples. ↩

-

I just stuck in

(0..0)as the span of the EOF token, mostly because we don't actually use that span anywhere and I couldn't be bothered. Since we have access to all previous spans, it is also not difficult to track the end of the last span and then go from there. Take that as an exercise for the reader, if you want. ↩